Imagine the music, singing and laughter, as the Cunningham family and their friends danced the night away at Lanyon Homestead. What music did they dance to? What were the popular songs of the mid-nineteenth century?

As part of the ‘Spring into the South Festival’ in 2020, music researcher Grace Chan performed a selection of pieces from a rare collection of colonial 1850s piano sheet music as part of a reimagining of the colonial soundscape at Lanyon Homestead. The breadth of musical activity in New South Wales from the start of European settlement and the volume of music that was brought to the Colony, reflected the importance of music to the colonists and their social and domestic environments.

Singing and Dancing at Lanyon Homestead

Scottish emigrants Andrew and Jane Cunningham built Lanyon Homestead in 1859. A year later, Jane’s sister, Sarah Jackson, joined the family after emigrating to New South Wales. Sarah lived at Lanyon for the next twenty years and was in high demand as a pianist. She accompanied dances that continued into the early hours of the morning, with couples dancing on the veranda during the warmer months and inside during winter.

.png)

An Evening At Yarra Cottage, Port Stephens, painted by Maria Brownrigg in 1857 (National Portrait Gallery)

The piano would have also been central to the family’s domestic entertainment. In 1857, Maria Brownrigg painted ‘An Evening At Yarra Cottage, Port Stephens’ that shows her six children in the drawing room of their home. Her son, Marcus, is at the piano. Apart from being a very rare painting by a female artist from this period, it also shows a detailed depiction of colonial life, including their tastes in fashion, decorative furnishings and family pastimes. This painting is now part of the National Portrait Gallery collection. It is easy to imagine a similar scene in the drawing room at Lanyon Homestead.

Researching colonial music and the domestic setting at Lanyon Homestead, Jennifer Gall writes:

Parlour music would have included a broad repertoire of piano solos written by 19th century art music composers, light opera and popular songs for voice and piano and albums of traditional Scottish and Irish vocal and instrumental music arranged for piano and perhaps one or two other instruments and voice.

This was certainly reflected in a volume of privately bound piano sheet music that was collected by a girl, named Emily Strong, who grew up Sydney during the 1840s and ‘50s. The survival of this privately owned collection of music provides a rare insight into the personal and popular tastes of this period.

Emily’s Songs

Emily Strong (1833-1860) was born into a musical family. Her parents were English emigrants and Emily was born within weeks of the family landing in Van Dieman’s Land, enroute to Sydney. Her father was a tailor and an amateur theatre musician. Her older brother, George Strong Jnr, was a violinist, theatre musician and composer, who played in theatre orchestras with George Hudson, a Sydney music publisher.

Emily’s collection of music included a mixture solo and piano works. Researching the history of the Strong family and Emily’s sheet music, Graeme Skinner noted that the many of the Sydney prints in Emily’s album were published by George Hudson. The music collection also included original Australian content, with several pieces by Isaac Nathan, who wrote, composed and produced the first opera in Australia. Handwritten ornaments on some of the Nathan’s songs suggests that Nathan might have been Emily’s music teacher.

The range of popular and classical music reflected the imported tastes of the nineteenth century colony. Pieces like La militaire quadrille – Polkas arranged for pianoforte – National Schottisch the German Dance – Lady O’Connels Waltz – the Aurora Waltz – Dos Santos’ Quadrilles – and other numerous quadrilles, waltz and polkas reflected Emily’s love of dance music. It seems young people prefer this genre no matter which historical period they belonged to.

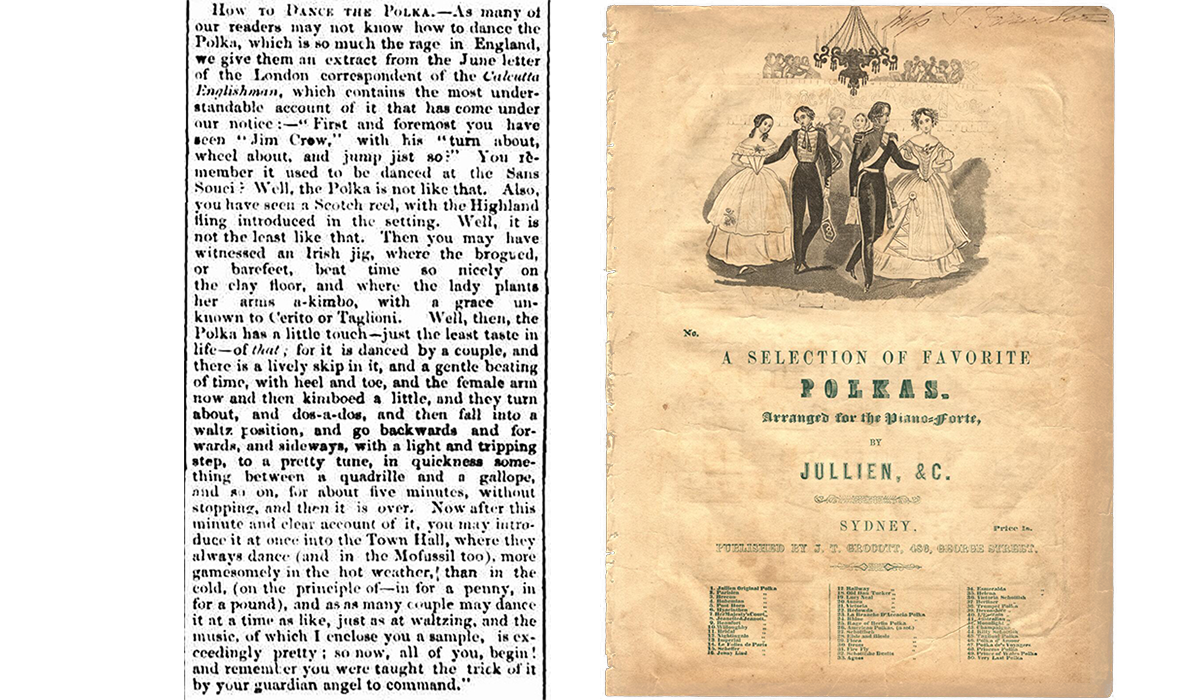

It is easy to imagine some of these polkas, waltzes and quadrilles being played by Sarah Jackson for her Cunningham nieces, nephews and friends at Lanyon Homestead. The polka was a particularly popular dance that started in Paris in the 1840s. In 1844, The Sydney Morning Herald described how this new dance was not like a ‘Jim Crew’ or a ‘Scotch reel’, but had a touch of the Irish jig and:

danced by a couple, and there is a lovely skip to it, and a gentle beating of time, with a heel and toe, and the female arm now and then kimboed a little, and they turn about, and a dos-a-dos, and then fall into a waltz position, and go backwards and forwards, and sideways, with a light and tripping step, to a pretty tune, in quickness something between a quadrille and a gallope, and so on, for about five minutes, without stopping, and then it is over.

The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 November 1844. Cover of A Selection of Favourite Polkas. Arranged for the PianoForte, by Jullien, &C. (National Library of Australia).

Emily’s volume of music also included popular classical pieces and operas that were arranged to allow for their domestic setting performances. These included the pieces such as the Overture to the opera Il Trancredi – Beethoven selection for pianoforte – Mozart’s Overtures. And sprinkled amongst these pieces are melancholic love songs, for young romantic yearnings such as – By the sad sea waves – Tell him I love him yet – Will you love me then as now?

Emily Strong was only twenty-six-year-old when she died, a few days after giving birth to her third child. She was married to Harold McLean, Gold Commissioner of the Western Goldfields and living in Sofala at the time. Emily would have had a comfortable married life, but it is easy to imagine the isolation and possible loneliness of being a young woman in the goldfields, separate from her family and friends in Sydney. Did Emily turn to her music in times of solitude? Exploring her music and imagining her short life provided a poignant insight into the colonial female experience.

Recreating Colonial Music at Lanyon Homestead

In 2020, Lanyon Homestead was part of the Floriade Reimagined Community Program, following the cancellation of Floriade in Commonwealth Park due to the Covid-19 pandemic. The planting of thousands of tulips, daffodils and poppies provided the magnificent Springtime backdrop for the ‘Spring into the South Festival’ at Lanyon Homestead in Spring 2020.

Grace Chan performing ‘Home Sweet Home’ on harmonium at Lanyon Homestead

The program of events included Grace Chan (Conservatorium of Music, University of Sydney) performing a selection of pieces from Emily Strong’s music album on the 1840s Broadwood piano in the Lanyon Homestead 1860s drawing room and on her own harmonium in the Lanyon gardens. In a year where the Covid-19 pandemic decimated the performing arts, it was wonderful to have a live (Covid-safe) concert despite strict restrictions.

Grace Chan performing The Drum Polka on the Broadwood piano at Lanyon Homestead

Grace performed with the French doors of the sitting room opened and timed to coincide with art workshops being held on the veranda. The sound of the piano immersed the artists in nineteenth century music as it drifted onto the veranda and into the garden for visitors to enjoy. It was a magical experience hearing the homestead come to life – and to imagine if these pieces were similar to those practiced and performed by the Cunningham family. For her performance, Grace selected a range of lively dance pieces (such as the Drum Polka by Jullien, & c.) and more calming melodies that were suited to the Broadwood piano (like ‘Will you love me then as now’, published by G. Hudson).

The Drum Polka, from A Selection of Favourite Polkas. Arranged for the PianoForte, by Jullien, &C. (National Library of Australia)

We do not know what type of piano that the Cunningham family owned at Lanyon Homestead. The 1840s Broadwood ‘Cottage Upright’ piano currently displayed at Lanyon Homestead is representative of pianos present in the colony during the mid-nineteenth century. An imported piano was advertised for sale in The Sydney Gazette for an eye-watering sixty guineas in 1803, nearly triple the price in England. Broadwood pianos were manufactured in England and were noted for their reliable design.

It is also possible that the Cunningham family might have owned an Australian manufactured piano, with the first locally manufactured pianos starting in 1834 by John Benham and followed by other local manufacturers. The presence of a piano at Lanyon was indicative of the family’s middle-class wealth. In a time before radio, televisions or iTunes, musical instruments were central for entertainment and cultural pursuits in nineteenth century colonial life.

Playing on an unfamiliar instrument is always challenging. Playing on an unfamiliar 180-year-old instrument that changes tone and touch with the weather is even more so. But relatively isolated colonial homesteads would not have had perfectly tuned pianos, and the recordings of Grace’s performance reflects the domestic and physical environment of colonial music, and the temperamental character of period instruments.

Grace described the combination of playing Emily Strong’s collection of music on the 1840s Broadwood, within a historical setting and ‘the synergy of artists creating around me’, as an ‘imaginative boost’. For Grace, it also demonstrated the contrast of:

how it felt to be in the house without music or sound - the sense of isolation for a woman in that situation and the importance of music as a nourishment.

For visitors, it was an opportunity to reimagine the life and sounds of the families and people who lived, worked and socialised at Lanyon Homestead.

Emily Strong’s Playlist Performed at Lanyon Homestead

*only known existing copy is in Emily’s album

Overture to the opera Il Tancredi *

(Rossini/ Grocott, Sydney, c.1850)

La militaire quadrilles

(Daniell / Wilson, Rushcutter’s Bay, 1848)

Devonshire Polka

(Oury / Hudson, Sydney c.1850)

The Drum Polka

(Jullien / Grocott, Sydney c.1850)

Polka des voyageurs*

(?Wallerstein / Grocott, Sydney c.1850-51)

The National Schottisch the German dance

(Musical Bouquet no. 189, n.d. London [1849])

The Rataplan

(Donizetti / Musical Bouquet 197, London, 1849)

Di Tanti palpiti with variations

(Rossini-Dale / Duncombe, London, c.1840)

The aurora waltz

(Labitzky / Musical Bouquet 62-63, London, 1846)

Queen of evening

(Nathan / Cramer, Addison, and Beale, & c. London, 1837)

The Sydney Corporation quadrilles

(Ellard / Ellard, Sydney, 1842)

Dos Santos' quadrilles *

Les Etoiles

(Dos Santos / Rolfe, Sydney / c.1842-43)

La reine d'ocean quadrilles *

(Dos Santos / Rolfe, Sydney / c.1844-45)

Les Portugaises quadrilles *

(Dos Santos / Rolfe / c. 1842-43)

Mozart's overtures - The Magic Flute *

(Mozart / Dale, London c.1820s)

Beethoven selection for piano forte - Rondo from Symphony in C *

(Beethoven / Dale, London, c.1820s)

Ladybird

(Nathan / Falkner, London, 1831)

REFERENCES

The Drum Polka, from Selection of favorite polkas arranged for the pianoforte, by Jullien &C (National Library of Australia – available online http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-165680189).

Emily Strong’s collection of music scores for piano, 1840-1850 (Fisher Library Rare Books, University of Sydney).

Sydney Morning Herald, 19 November 1844.

Gall, Jennifer, ‘Listening to the Past: The context for music at Lanyon Homestead’ (prepared for ACT Historic Places, 2016).

Skinner, Graeme, ‘Emily Strong and her album’, (https://www.sydney.edu.au/paradisec/australharmony/strong-george-and-family.php#emily ).

About the Author

Dr Anna Wong is the Director of ACT Historic Places. Her doctorate examined the historical evolution of the house museum in Australia, and the representation of national identity and community values through the heritage conservation movement. Anna also enjoys exploring music and food histories, and the social history stories they tell.